How Vidstack's Journey is Shaping Video.js v10

This is part of a series on the making of Video.js v10. See also: Wesley on how Media Chrome's HTML-first architecture is evolving and Sam on how Plyr's design polish is shaping the UI.

Between Vime and Vidstack: 9 billion CDN requests. 7 million NPM downloads. 6,200 GitHub stars. Over 200 releases. Now I'm building something better.

The beginning

My journey started in 2020 with a library called Vime. At the time, video players like Video.js and Plyr felt like black boxes. You dropped a script on your page and hoped for the best. Customization meant fighting against the library rather than working with it.

<!-- The widget era: drop this and you're done -->

<video class="video-js" controls data-setup="{}"></video>

<script src="<https://vjs.zencdn.net/8.23.4/video.min.js>"></script>

<!-- But good luck building something custom -->Meanwhile, frameworks like Svelte were showing us what compiled components could be. Small, composable pieces. State that flowed predictably. A JS compiler target. I remember thinking: this is how we should build players. Why isn't anyone doing this?

So I built one.

I posted Vime on Reddit and it took off. People were actually using it. My first real open source project, and developers were building video players with it. That feeling never gets old.

In retrospect, a lot of the excitement was probably just that I was using Svelte — the exciting new kid on the block.

But honestly, I'd created something awkward. A bespoke plugin system that didn't feel natural to anyone. I hadn't really solved the problem. I'd just moved it around.

const player = new Player({

target,

props: {

plugins: [ActionDisplay, Keyboard, Tooltips], // 👎 awkward

},

});Video is actually hard

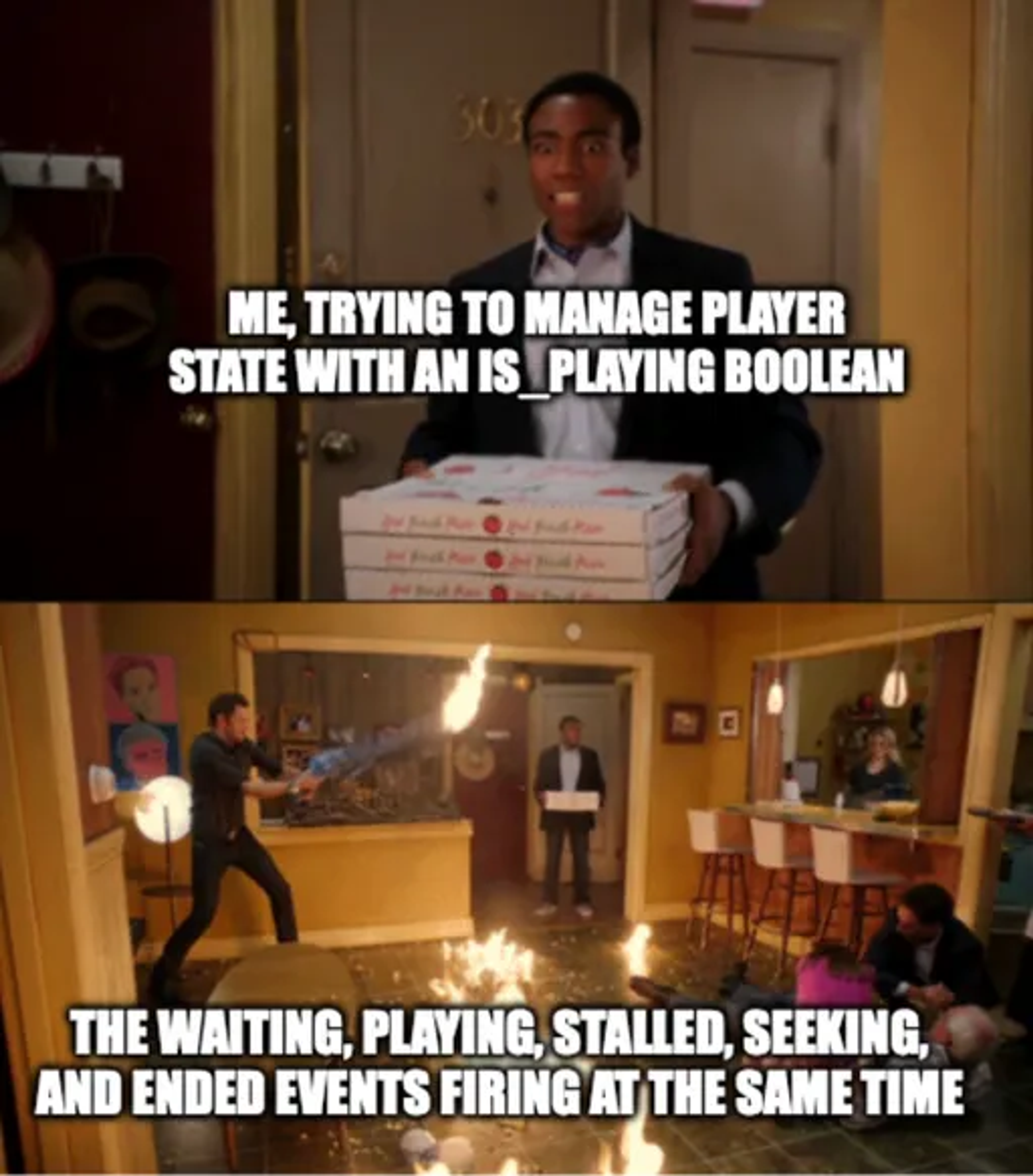

Here's what I learned about why video breaks people's expectations.

Events ≠ state. The video element fires events, but they're inconsistent across browsers. They might fire, they might not, they might fire in rapid succession. Wiring up UI to these events is fragile. Tracking whether they came from a user or the media itself is even more challenging.

And that's before you get to the features people actually need: captions in multiple formats, streaming protocols, adaptive bitrate, ads, DRM, analytics, and so on. It spirals quickly.

The old players solved this by hiding everything. You got a widget. It worked (mostly). But if you wanted something different, you were on your own.

Vidstack at Reddit

In 2021, Dave Furfero reached out on Discord. At the time he was a Staff Software Engineer at Reddit, dealing with buggy video implementations across their platform. He'd built something internally with a similar architecture to what I was attempting with Vime. He approached me to join them and integrate my project, so I said yes.

That's where Vidstack was born. Reddit was experimenting with Lit at the time, so we built a web component library. Over a few months, we developed the architecture that would define Vidstack: state management with signals, request controllers, the natural state-down-events-up flow.

Working with Dave was incredible. We were riffing on ideas, building something that felt genuinely new. Coming out of Reddit, we had a solid player. I was proud of it.

I kept pushing on it for a few more years. Eventually Vidstack became something I was really proud of: a Radix-like component library for video. Hooks, compound components, accessibility baked in. Less black box, more building blocks.

This was the vision I'd been chasing since Vime. But getting there meant solving a harder problem first.

The component era promise

When React and Vue emerged, they introduced something powerful: the ability to decompose your UI into small, reusable pieces that each manage their own state and behavior.

That's the player I wanted to build. Not a widget you configure, but components you compose. But as a library author, I was stuck on the hard question: how do you build and distribute components that work everywhere?

Web components seemed like the answer. Write once, ship everywhere. Custom elements, Shadow DOM, HTML templates.

Steven Heffernan (Heff) saw this coming a decade ago. He gave a talk at Demuxed 2015 about web components for video, then made his first Media Chrome commit in 2018. Meanwhile, I was just getting started — Vime moved to web components in 2020, and Vidstack followed when I joined Reddit in 2021.

For a while, it felt like we'd figured it out.

We could compose components. Customize individual pieces like a fullscreen button or time slider. We even had styling APIs that worked with Tailwind. It was better than the widget era.

But reality kept pushing back.

<media-menu>

<media-menu-button aria-label="Settings">

<media-icon type="settings"></media-icon>

</media-menu-button>

<media-menu-items placement="top" offset="0">

<!-- Menu Items + Submenus -->

</media-menu-items>

</media-menu>The friction

We build applications with components. Things with complex state, sophisticated interactions, lifecycles tied to framework rendering.

Trying to force modern component patterns into the constraints of the DOM created constant friction. Awkward lifecycles. Painful SSR workarounds. Subpar tooling. TypeScript support that ranged from bad to nonexistent.

Ryan Carniato, Rich Harris, Evan You, and others documented similar struggles. Web components felt like another framework you had to fight against rather than something idiomatic to what you were already using.

Even when Web Components worked, there was an unspoken cost. You were asking teams to learn a second component system. Shadow DOM changes how you debug and style. Slots change how you compose. And theming often turns into a grab bag of escapes like CSS variables, ::part, and ::slotted. None of it is a dealbreaker on its own, but together it’s another set of rules you have to internalize before you can ship.

In Vidstack, we avoided Shadow DOM. We shipped JSX types for Vue, Svelte, and Solid. We built a dedicated framework to improve performance and bindings. But the fundamental mismatch remained.

What Vidstack got right

Despite the friction, a lot worked. Really worked.

The state management architecture held up. A request/response model where state flows down and events bubble up with triggers attached. We built it this way at Reddit to precisely track requests from the moment a user clicked play to the media response. You could trace any state change back to what caused it.

const remote = new MediaRemoteControl();

button.addEventListener('pointerup', (event) => {

// Tracing this play call back to this pointer event.

remote.play(event);

});Exposing state as data attributes and CSS variables was a win. Developers could style based on data-paused or data-bufferingwithout touching JavaScript.

The Radix inspiration paid off. Compound components like TimeSlider.Root, TimeSlider.Track, TimeSlider.Thumb felt familiar to developers already using modern UI libraries. People told us it felt like a natural extension of their app rather than a foreign widget. That was everything. That was the whole point.

<TimeSlider.Root className="group relative inline-flex ...">

<TimeSlider.Track className="relative ring-sky-400 z-0 ...">

<TimeSlider.TrackFill className="bg-indigo-400 w-[var(--slider-fill)] ..." />

<TimeSlider.Progress className="absolute w-[var(--slider-progress)] ..." />

</TimeSlider.Track>

<TimeSlider.Thumb className="absolute left-[var(--slider-fill)] top-1/2 ..." />

</TimeSlider.Root>Maverick, our underlying framework system, was incredibly performant. We built a powerful context and reactivity layer on top of signals that could bind to any host framework. Fine-grained updates meant only what needed to update would update, and the work stayed computationally cheap.

The breadth of features mattered too: HLS, DASH, YouTube, Vimeo, captions in multiple formats, chapters, thumbnails, keyboard shortcuts, picture-in-picture. All accessible, all working across providers through a unified API.

But we hit walls. Hard ones.

What Vidstack got wrong

The monolithic design never fully went away. Despite modular architecture, the "player" as a unit was still hard to customize at the deepest level. The store grew bloated. We tracked too many state properties. Our state and request controllers were growing out of control, the logic was hard to follow. Some parts of our state management were redundant, some rarely used. Performance-conscious users noticed.

// Monolith 👎

const mediaState = new State<MediaState>({

artist: '',

artwork: null,

audioTrack: null,

audioTracks: [],

autoPlay: false,

// 103 other props...We had a slots prop on the React side, but that's not the same as complete control of source. On the Web Component side, we avoided Shadow DOM to reduce friction for developers, which meant no slots at all. Users wanted to swap individual controls into our skins but couldn't. Build from scratch or accept the defaults.

// Constrained 👎

<DefaultVideoLayout

slots={{

playButton: CustomPlayButton,

// 74 other slots positions...

}}

/>Maintaining web components alongside a React library required constant coordination. The Maverick framework (our signals library) added mental overhead for contributors. They had to learn a bespoke system before they could help.

And users kept asking for the same thing: direct source access to skins. Not imports they couldn't modify, but code they could own. The shadcn model.

Reaching the limits

By early 2025, I knew we'd hit the ceiling. Financially and technically.

I'll be honest: building a video player library at this scale as a solo maintainer isn't sustainable. The web component friction wasn't going away. The maintenance burden across frameworks kept growing. I was stretched thin.

Vidstack had hit the limits of its own architecture — Maverick, the store and controller design, the attempt to abstract across every framework. Meanwhile, Heff and his team were building Media Chrome and hitting a different limitation. Web components can get you far, but they'll never feel 100% idiomatic in React, Vue, or Svelte. Different paths, same conclusion.

My son was born that year. Suddenly the stakes felt different. It was time to find something sustainable, something with a team behind it.

Matt would check in on me from time to time. When we talked about joining forces, it clicked. I joined Mux because the alignment was obvious. Heff and the team want to build incredible player libraries. Mux wants to serve developers. Great team, great brand, developers first. It felt right immediately.

What we're building now

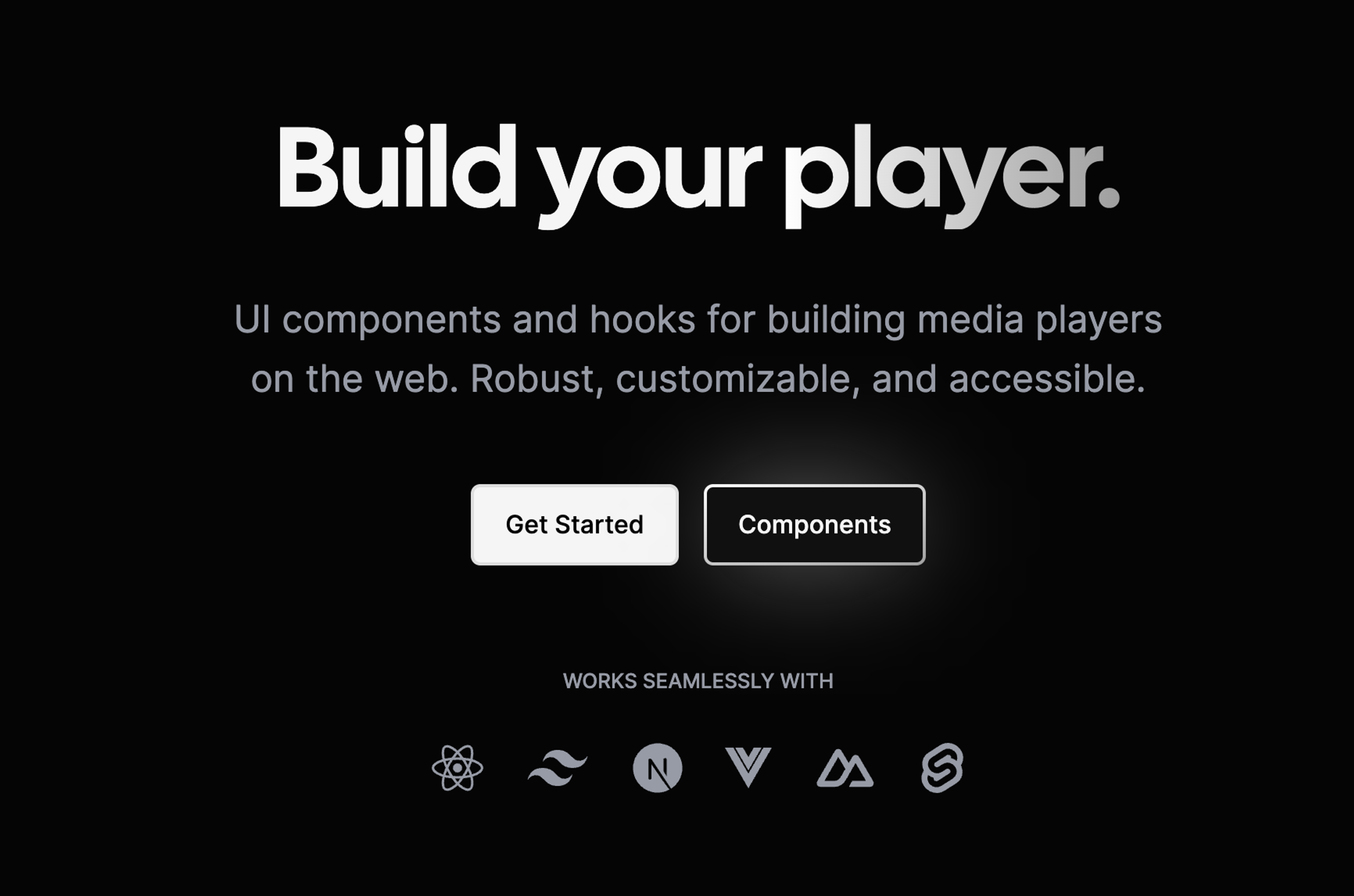

Video.js v10 is the convergence. Everything that made Vidstack great, without the constraints.

Here's why I'm excited about Video.js v10!

We're taking the composition patterns that worked in Vidstack and refining them. Better APIs learned from Base UI, like render props instead of asChild for cleaner TypeScript. Components that feel native to each framework rather than web components shoehorned in. No more fighting.

// Bring your own element — Framer Motion, Radix, Base UI

<PlayButton

render={(props, state) => (

<motion.button {...props}>

{state.paused ? <PlayIcon /> : <PauseIcon />}

</motion.button>

)}

/>The core state management is rebuilt from scratch. Async store, no external controllers, guards, and plenty of exciting new features. Composable, modular, extensible. Completely typed based on your configuration. You can see where it’s headed under the hood.

// Composable: slices determine what's available

const { Provider, usePlayer } = createPlayer({

slices: [playback] // → usePlayer now has play(), pause()

});

// Or, use a preset

createPlayer(presets.backgroundVideo);We're building a compiler that takes React and Tailwind as a lingua franca and outputs to other framework and styling systems. Do the math: 6 JavaScript frameworks, 3 CSS frameworks, 36 components. That's 648 variations. The compiler makes that maintainable. Without it, it's brutal — I know from Vidstack.

We're finally doing skins the right way. shadcn-style. Copy the source, own the code, customize freely. Purpose-built for specific use cases: Web, Streaming, Swipe, and more. Every internal exposed for modification. This is what users kept asking for. We're finally delivering it.

And React Native. We're building with that in mind from day one. Core logic separated from DOM, so the same player brain can power web and native.

Most importantly: true modularity from the ground up. Not a monolith made modular, but modularity as the foundation. Import only what you need. Tree-shake everything else. Extend only what you want. A streaming engine where you pay only for the features you use. This is what I've wanted for six years.

What this means if you're using Vidstack

This isn't abandonment. It's evolution.

The patterns you loved are coming forward, without the constraints that held it back. Radix-like composition. Framework-native feel. Comprehensive accessibility. The breadth of features.

The pain points are being addressed at the architectural level. Skin customization limits. Web component friction. Streaming bundle size. All of it.

We'll publish a migration guide when v10 launches.

What comes next

I know with certainty we're building something better in Video.js v10.

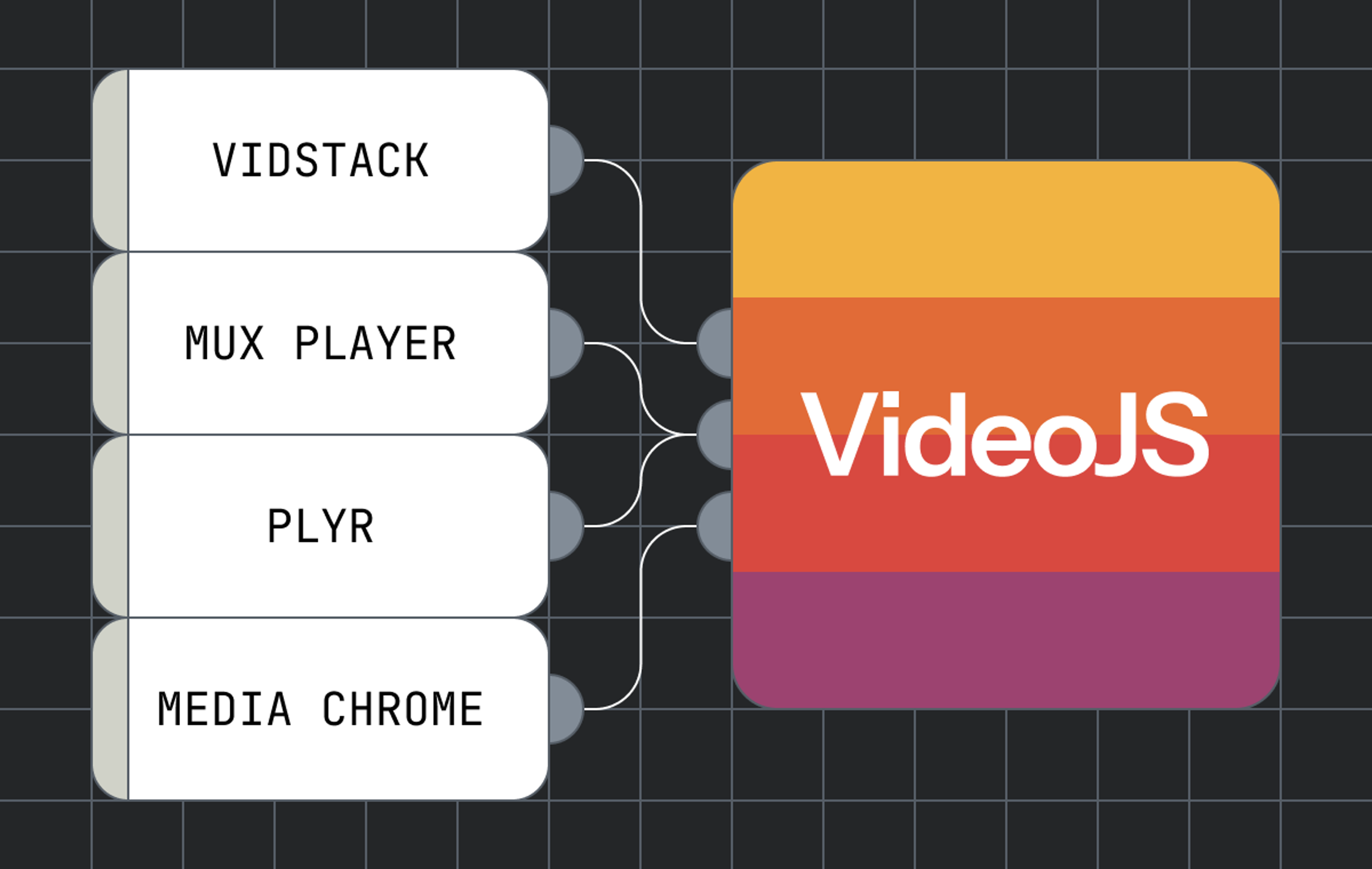

The lessons from Vidstack — what worked, what didn't, what users actually needed — are all feeding into this. Vidstack, Media Chrome, and Plyr. Three projects, now building together.

A truly composable, modular, and extensible player. Built from the bottom up. For the first time.

We're actively working on the Video.js v10 Alpha, along with a fresh site design. You can follow along on our roadmap — we're expecting to drop Alpha early February.

Six years of learning. Decades collectively. Now we're building something better.