Earlier this year, I thought I had built the worst video player on the internet. A badge to be proud of, for sure. I flaunted it daintily, humbly telling anyone who would listen, submitting talks to conferences about how it was built, donning the crown during each and every team sync.

My reign didn't last long. When we ran Mux's Worst Player competition earlier this year, I scoffed at the idea of someone outperforming underperforming my work. Fat chance. I write awful code (and even worse blog posts).

Then, out of nowhere, in the final few hours before the contest deadline arrived, we received a truly terrible submission from Christina Martinez. I bit my lip as the truth slowly dripped down to cover me like a caramel apple: this was bad. Really bad. So bad, it's good. In fact, it was good enough to win Christina the grand prize; a paid trip to Vercel Ship.

Now, with Christina's killer storytelling and documenting, you, too, can see how bad it really is. Read on. You can check in on my bruised ego later.

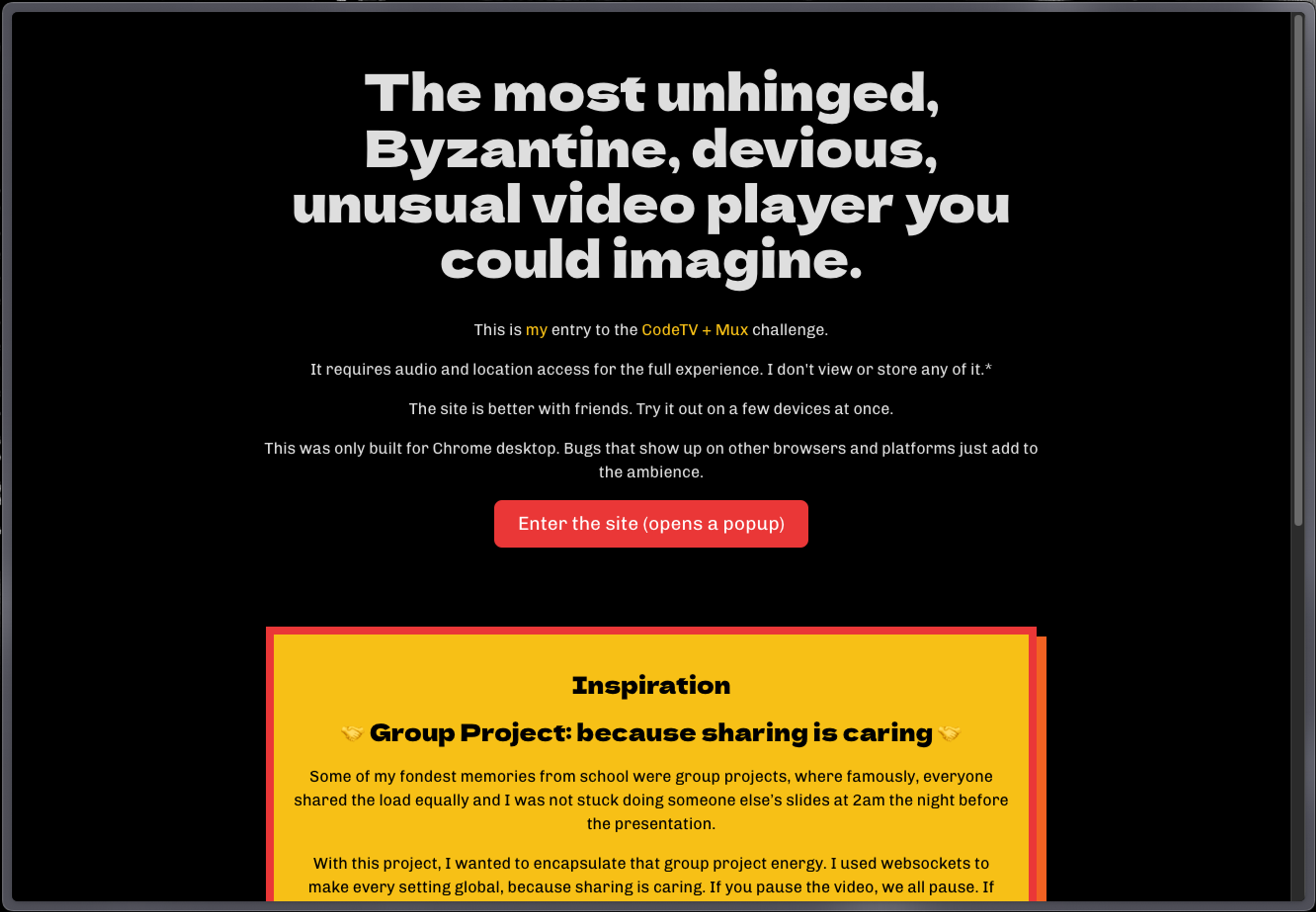

I built the worst video player on the internet, and I'm here to show you how I built it. For science.

Warning: The stunts you are about to see were performed by a professional at writing bad software. Don't try this at home.

This summer, CodeTV and Mux hosted an online competition to see who could build the most unhinged, Byzantine, devious, and unusual video player imaginable. I've been known to write my share of bad software, so I knew I had to enter right away.

When Dave Kiss emailed me to say that my submission was "truly awful" and invited me to New York City for Vercel Ship as the grand prize, I was thrilled.

Let's walk through how I built the worst video player imaginable.

The inspiration

To try to find inspiration for this project, I reflected on the top ten most painful experiences of my life. At least three of them were those group projects we all dreaded in school. You know the ones: Brad didn't do his slides because he had intramural lacrosse practice; Angie promised she'd finish her part yesterday, but now she's completely ghosted you. You've never met the third member of your group, and you're not sure they've ever shown up to class.

I wanted this video player to encapsulate that same energy. It's the feeling of relying on others. Others who will inevitably let you down and ruin your week. No, my mental health is fine. Why do you ask? Let's get back to the video player.

Sharing is caring (featuring WebSockets)

To accomplish my goal of encapsulating group project energy, I needed a way to make every setting global. I wanted each user's actions to impact everyone else's experience, because sharing is caring.

Enter: WebSockets.

WebSockets are a way to communicate in both directions: a client—the website—can communicate with the server, and the server can send data back down to the client. It’s almost like an always-on, two-way API.

To set up a simple WebSocket server, I used a Node.js WebSocket library called ws.

I imported the package and initialized a new WebSocket server on port 8080:

import { WebSocketServer } from "ws";

const wss = new WebSocketServer({ port: 8080 });Websockets are event-driven, so I needed to define what's supposed to happen when various events occur.

First, I wrapped everything in an on connection call to ensure that all of the events are set up when a client first connects to the server:

wss.on("connection", (ws) => { ... });The events that I set up inside of this on connection call will stay set up as long as the connection is open. WebSocket connections are interrupted when you lose internet or leave the page, but otherwise should generally stay open while you stay on the site.

Inside, I set up two types of events: message and close.

Message received 🫡

The event that occurs when you send and receive text data is called a "message." When receiving new messages, I wanted to broadcast the data to all of the clients. That would ensure that if one person takes an action, all clients would respond accordingly.

Rather than blindly sending along any message, I needed to check that it's valid JSON:

try {

const messageStr = message.toString();

const parsed = JSON.parse(messageStr);

if (typeof parsed === "object" && parsed !== null && parsed.type) {

...

} else {

console.warn(

"Received invalid message format (missing type):",

parsed

);

}

} catch (error) {

console.error("Received invalid JSON message:", error);

}Now I could send the message to each client:

wss.clients.forEach((client) => {

if (client !== ws && client.readyState === 1) {

client.send(messageStr);

}

});In the front end, I handled each WebSocket update and updated the state of the video player accordingly. More on that later.

Here's the on message call:

ws.on("message", (message) => {

try {

const messageStr = message.toString();

const parsed = JSON.parse(messageStr);

if (typeof parsed === "object" && parsed !== null && parsed.type) {

wss.clients.forEach((client) => {

if (client !== ws && client.readyState === 1) {

client.send(messageStr);

}

});

} else {

console.warn(

"Received invalid message format (missing type):",

parsed

);

}

} catch (error) {

console.error("Received invalid JSON message:", error);

console.error("Raw message:", message.toString());

}

});Now, let's keep in mind that this was my first time using WebSockets, I hacked together this code in my free time not expecting it to go anywhere, and I was more interested in making something that sort of worked rather than something that was technically flawless. If you're interested in building a production-ready WebSocket server, you should look elsewhere for a guide.

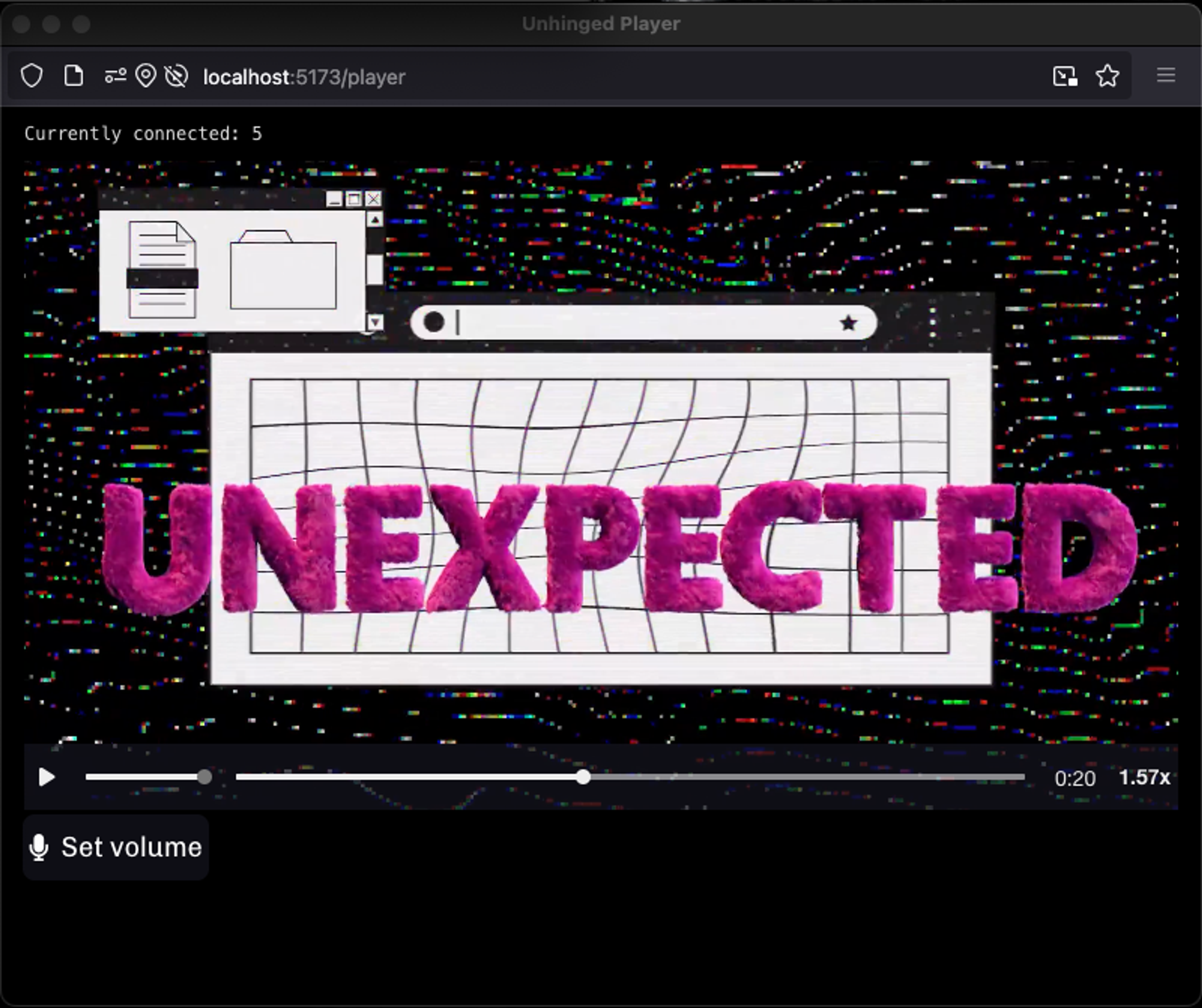

The world's worst video player

The landing page

I wanted this video player to have a series of extremely cursed features:

- Global play and pause state. If you pause, we all pause.

- A complicated playback speed that's difficult to change, based on the average latitude of all users.

- Global volume control, so that all users watch the video at the same volume. The volume is set by making a noise inversely proportional to the sound you want. For example, if you're in a library and you'd like a quiet volume to fit the environment, you must scream.

- Strange seeking behavior. When a user seeks the video, the window helpfully moves around on their screen.

- A count of currently connected users, so users can see how many others are influencing these values.

A few of these feature ideas required inputs that the user has to grant to a website, such as location (for latitude) and microphone input (for the volume control). Likewise, moving the window around the screen using window.moveBy() is only possible when the window has been created using window.open(). For those reasons, I made a simple intro page that explains the project and what inputs I need access to. The page is basically just a bunch of text elements and a button that opens a new window using a simple function:

const openNewWindow = () => {

window.open("/player", "", "width=800,height=600,left=500,top=100");

};The player

I started the bulk of the front end by adding a Mux Media Chrome video player to my Player component. The contest page helpfully included a quickstart template, which I copied and pasted into my app:

import { MediaController } from 'media-chrome/react';

import { useRef } from 'react';

import MuxVideo from '@mux/mux-video-react';

interface PlayerProps {

isPlaying: boolean;

}

const Player = ({ isPlaying }: PlayerProps) => {

const videoRef = useRef<HTMLVideoElement>(null);

const togglePlay = () => {

if (videoRef.current) {

if (isPlaying) {

videoRef.current.pause();

} else {

videoRef.current.play();

}

}

}

return (

<>

<button onClick={togglePlay}>{isPlaying ? 'Pause' : 'Play'}</button>

<MediaController id="player">

<MuxVideo

ref={videoRef}

playbackId="PLtkNjmv028bYRJr8BkDlGw7SHOGkCl4d"

slot="media"

crossorigin

muted

/>

</MediaController>

</>

);

};

export default Player;I removed the TypeScript annotation with a quickness. Sorry, I know, type safety and all that. I just didn't want to deal with types for this. Plus, the purpose of this was to make the worst app, and what's worse than a weakly-typed language that was famously prototyped in 10 days?

The Mux video player was good to go out of the box. I just needed to install a couple of packages (npm i media-chrome/react @mux/mux-video-react) and it just... worked.

It worked too well, actually. I needed to make it worse.

You pause, we all pause

I wanted to use my WebSocket server to add a global play and pause state to the video. If one user pauses, the video pauses for everyone.

First, I wanted custom play and pause buttons. With the Mux Media Chrome tool, customizations to the player's styling are easy to make. I dropped my Font Awesome icons into the button slots, and Mux controls which icon to show depending on the video's play state.

<MediaPlayButton notooltip>

<span slot="pause">

<FontAwesomeIcon icon={faPause} />

</span>

<span slot="play">

<FontAwesomeIcon icon={faPlay} />

</span>

</MediaPlayButton>Next, I needed to listen to the video play state and add custom behavior when the video is played or paused.

useEffect(() => {

const video = videoRef.current;

if (video) {

video.addEventListener("play", handlePlayPause);

video.addEventListener("pause", handlePlayPause);

return () => {

video.removeEventListener("play", handlePlayPause);

video.removeEventListener("pause", handlePlayPause);

};

}

}, [handlePlayPause]);I defined a handlePlayPause function, which finds the video, checks whether it's playing or paused, and sends a new message to the WebSocket server.

const handlePlayPause = useCallback(() => {

if (!videoRef.current) {

console.error("Video reference is not set.");

return;

}

let newIsPlaying = videoRef.current.paused ? false : true;

setIsPlaying(newIsPlaying);

if (typeof window === "undefined") {

console.log("window is undefined, skipping WebSocket message");

return;

}

if (socket && socket.readyState === 1) {

socket.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "playback",

isPlaying: newIsPlaying,

})

);

} else {

console.error("WebSocket is not open. Cannot send message.");

}

}, [socket]);Before using the WebSocket, though, I had to connect to it from the front end.

I created a new connection, using a local version during development, and the production URL for the final product. I also kept track of socket in a state variable so that I could use it (e.g. in the code snippet above).

const websocketUrl =

import.meta.env.MODE === "production" ?

"https://mux-video-player.onrender.com" :

"ws://localhost:8080";

const ws = new WebSocket(websocketUrl);

setSocket(ws);When a message is received from other users broadcasting a change in the player state, the app does some parsing and validation before handling events with a type of playback. This code does the same operation as the Play/Pause button: it sets the isPlaying state and uses the videoRef to play or pause the video player.

if (data.type === "playback") {

setIsPlaying(data.isPlaying);

if (videoRef.current) {

data.isPlaying ?

videoRef.current.play() :

videoRef.current.pause();

}

}Playback speed for maximum longitudinal equality

I had a dilemma when it came to playback rate. A point on the earth spins faster at the equator and slower the farther North or South you get. To solve this problem, I adjusted the playback rate to be a global average value based on the latitude of all connected users. To influence this value, a user must move to a different latitude.

After connecting to the WebSocket server from the front end, I call the function getGlobalPlaybackSpeed, passing in the WebSocket connection:

ws.onopen = () => {

setTimeout(() => {

getGlobalPlaybackSpeed(ws);

}, 1000);

};It needed to happen after a slight delay, because before doing this calculation in the front end, I need to know what the existing global playback speed is. To accomplish that, I added some logic to the WebSocket server such that it reports the global average latitude value to the user just after a connection is made.

if (globalAverageLatitude !== null) {

ws.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "globalAverageLatitude",

averageLatitude: globalAverageLatitude,

})

);

}The front end is set up to handle globalAverageLatitude message types, like so:

if (data.type === "globalAverageLatitude") {

const newLatitude = data.averageLatitude ?? 0;

setAverageLatitude(newLatitude);

if (newLatitude > 0 && videoRef.current) {

const roundedPlaybackSpeed =

getRoundedPlaybackSpeedFromLatitude(newLatitude);

videoRef.current.playbackRate = roundedPlaybackSpeed;

setPlaybackSpeed(roundedPlaybackSpeed);

}

}Basically, it first calls getRoundedPlaybackSpeedFromLatitude, passing in the average latitude value, and then sets the video to the playback rate that that function returns.

Latitude values would make weird playback speeds. For example, Seattle is at 47.6061° N and São Paolo is at 23.5558° S (-23.5558). A place right on the equator, like the aptly named Ciudad Mitad del Mundo (Middle of the World City) in Ecuador, has a latitude value of 0. I needed to come up with a calculation to convert these values into playback speeds, which are generally between 0.50 if you're learning how to knit (ask me how I know) and 2 if you're a biohacking tech bro.

The thing is, I got a D+ in my college Calculus class, so I left the math to my good friend Copilot. Here's what it came up with:

const getRoundedPlaybackSpeedFromLatitude = (lat) => {

const distanceFromEquator = Math.abs(lat);

const playbackSpeed = 1 + distanceFromEquator / 90;

return Math.round(playbackSpeed * 100) / 100;

};This takes the absolute value of the latitude and maps those values to playback rate values between 1 and 2. Someone at the equator will have a playback rate of 1, and someone at the North Pole will enjoy the video at double speed. Yeah... Santa Clause being a biohacking gigachad actually checks out.

Then I needed to round the value so that users don't get a crazy playback speed like 1.54006777777.

Since the WebSocket is sending a message upon connection, the user will receive the global average latitude value just after connecting to the WebSocket. Then, after 1 second, the app uses the navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition browser API to prompt the user to share their location. Once permission is granted, it grabs the latitude value, so that the user's value can also be factored into the global value.

To calculate the new global average latitude value, it takes the existing global average, adds the new user's latitude, and divides that number in half in order to get a new value.

if (averageLatitude !== null) {

newLat = (averageLatitude + lat) / 2;

} else {

newLat = lat;

}

setAverageLatitude(newLat);Then the app will broadcast this new value as a WebSocket message, so that everyone else gets this updated value, too:

if (ws && ws.readyState === 1) {

ws.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "globalAverageLatitude",

averageLatitude: newLat,

})

);

}When a new average latitude value is received, the front end parses it using the same getRoundedPlaybackSpeedFromLatitude function. The resulting playback rate is set on the video using its ref:

videoRef.current.playbackRate = roundedPlaybackSpeed;Now everyone is the same again. No outliers. No individuality. Total hive mind. This is the goal.

You must scream

To set the volume, you need to make a noise inversely proportional to the volume you want. So, a loud sound produces a quiet volume setting. For example, if you're in a library and you'd like a quiet volume to match the environment, you must scream. This value is also shared between all users.

Setting this up was similar to the other shared values. For instance, I needed to handle incoming audioVolume events on the front end, setting the video's volume with the new value:

if (data.type === "audioVolume") {

const newVolume = data.currentVolume ?? 1;

setVolume(newVolume);

if (videoRef.current) {

videoRef.current.currentVolume = newVolume;

}

}I also added a new button to the video controls, which calls a getVolume function when clicked:

<button onClick={getVolume} title="Set volume (records a short audio snippet)" className="setAudioButton">

<FontAwesomeIcon icon={faMicrophone} />

</button>This getVolume function calls getAudioVolumeLevel, which kicks off a 3-second countdown before using another browser API, which starts streaming audio from the user's device:

const stream = await navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia({ audio: true });An audio analyser allowed me to inspect the audio coming in:

const audioContext = new(window.AudioContext ||

window.webkitAudioContext)();

const source = audioContext.createMediaStreamSource(stream);

const analyser = audioContext.createAnalyser();

analyser.fftSize = 256;

const dataArray = new Uint8Array(analyser.frequencyBinCount);

source.connect(analyser);Then, I calculated RMS, or Root Mean Square, which is a measure of audio loudness:

for (let i = 0; i < dataArray.length; i++) {

const val = dataArray[i] - 128;

sum += val * val;

}

const rms = Math.sqrt(sum / dataArray.length);

resolve(rms);After that, I needed to stop capturing audio, since I have the number that I wanted:

stream.getTracks().forEach((track) => track.stop());Here's what the getAudioVolumeLevel function looks like put together:

export async function getAudioVolumeLevel({ delay } = { delay: 3000 }) {

const stream = await navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia({ audio: true });

const audioContext = new (window.AudioContext ||

window.webkitAudioContext)();

const source = audioContext.createMediaStreamSource(stream);

const analyser = audioContext.createAnalyser();

analyser.fftSize = 256;

const dataArray = new Uint8Array(analyser.frequencyBinCount);

source.connect(analyser);

return new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(() => {

analyser.getByteTimeDomainData(dataArray);

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < dataArray.length; i++) {

const val = dataArray[i] - 128; // center around 0

sum += val * val;

}

const rms = Math.sqrt(sum / dataArray.length);

resolve(rms);

stream.getTracks().forEach((track) => track.stop());

}, delay + 500);

});

}The units here are also not a one-to-one correlation to video volume levels, which can be between 0 and 1. To translate the audio snippet's RMS into a volume, I used the following calculation:

const newVolume = Math.min(volume / 90, 1.0);And then, of course, I wanted the inverse of that, so I subtracted that value from 1 before setting our audio level and broadcasting it to everyone:

const inverseVolume = 1 - newVolume;

setVolume(inverseVolume);Here's what the final getVolume function looks like:

const getVolume = async () => {

if (typeof window === "undefined") {

console.log("window is undefined, skipping volume check");

return;

}

setGettingVolume(true);

const volume = await getAudioVolumeLevel({

const stream = await navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia({ audio: true });

const newVolume = Math.min(volume / 90, 1.0);

const inverseVolume = 1 - newVolume;

setVolume(inverseVolume);

if (socket && socket.readyState === 1) {

socket.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "audioVolume",

currentVolume: inverseVolume,

})

);

} else {

console.error("WebSocket is not open. Cannot send seeking event.");

}

};Seeking out the worst seeking behavior

I thought that it would be really convenient and helpful to move the window around the screen when the user seeks the video. This is helpful because it is.

For this, I used the Media Chrome MediaTimeRange component as the control, and called handleSeeking onMouseDown:

<MediaTimeRange onMouseDown={handleSeeking} />The handleSeeking function gets the currentTime on the video and passes it into a call to debouncedSeeking.

const handleSeeking = (event) => {

if (videoRef.current) {

const currentTime = videoRef.current.currentTime;

debouncedSeeking(event, currentTime);

}

};debouncedSeeking is a debounced function that moves the window left or right by 100 pixels, supposedly based on the difference between the new time and the current time.

const debouncedSeeking = debounce((event, currentTime) => {

const newTime = parseFloat(

event.target.getAttribute("mediacurrenttime")

);

const moveBy = newTime - currentTime;

moveWindow(moveBy > 0 ? 100 : -100, 0);

}, 300);I quickly found out by testing that the event.target's mediacurrenttime attribute and the videoRef's currentTime attribute were often the same value, so while sometimes the window would move around based on the direction the user seeks, sometimes it wouldn't. Rather than trying to fix the bug, I kept it as a feature, because it felt even more cursed for the window to move around the screen unpredictably.

I used window.moveBy to move the window left or right based on this unpredictable value:

const moveWindow = (moveByPx) => {

if (typeof window !== "undefined") {

window.moveBy(moveByPx, 0);

}

};Starting in Firefox 7, you can't use window.moveBy() on windows that the user created. You must first create the window using window.open(). That's the key reason that I showed an intro page before programmatically launching a popup via a button click (using window.open()), as described earlier.

We're all in this together 🤝

I thought that, unlike the typical group project, it would be nice to know upfront how many users are actively working toward the group's outcome. To make this visible, I added a count of how many users are live at any given moment.

When a new user connects, they broadcast a "connectedClients" message with the new number of connections:

wss.on("connection", (ws) => {

...

wss.clients.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === 1) {

client.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "connectedClients",

connectedClients: wss.clients.size,

})

);

}

});

...

});In the front end, we receive that number and store it in state:

if (data.connectedClients || data.type === "connectedClients") {

setCurrentlyConnectedUsers(data.connectedClients);

}And then simply display it in a paragraph element:

<p className="currentUsers">

Currently connected: {currentlyConnectedUsers}

</p>When the user disconnects, they broadcast another message, sharing the new user count (minus the departing user) with all other users:

ws.on("close", () => {

wss.clients.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === 1) {

client.send(

JSON.stringify({

type: "connectedClients",

connectedClients: wss.clients.size,

})

);

}

});

});This loops through each of the connected clients and ensures that each client is still ready to receive messages (i.e., it wasn't one that disconnected). Then, it sends a message with the updated number of connections, so each connected client is notified when someone drops off.

Conclusion

I learned a lot while working on this project. I got to use WebSockets for the first time, which was an adventure. I also got a solid intro to Mux's Media Chrome tool and how easy it is to work with. Next time I work on a project with video, Media Chrome will be my go-to tool for quick and easy customization. They didn't even tell me to say that, it's just true.

I'm so grateful to Mux for hosting this competition. I had a ton of fun putting this together and an even better time visiting New York for Vercel Ship. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Everyone that I met from Mux was so friendly and warm, and they turned me into a Mux fan for life.

And if you're reading this, odds are you're looking to build a video player. I wish you the best on your endeavors, and hope that your video player turns out better than mine. Or worse. I'd like to see you try.